American Folklore

The internet was supposed to spread information and elevate our understanding of the world. Instead it turned us into a primitive people, reliant on folk stories.

https://www.thebulwark.com/p/american-folklore

I know we should be talking about the possibility of a government shutdown and Elon Musk’s takeover of the Trump administration, but today I want to zoom out to 30,000 feet and look at how technology has influenced our politics in a totally unexpected way.

The dream of the internet was that it would create a high-information, high-trust society. Technology was supposed to make facts and primary sources immediately available to everyone, thereby ushering in an age of rationality and data-driven decision-making.

If you lived in Bumblefuck, Missouri, the internet meant that you were no longer beholden to the limited stream of news provided by your local paper, three broadcast networks, and assorted cable news players. You’d be able to see the information with your own eyes.

A Senate committee issued an important report? A scientific journal published a landmark study? You’d be able to sit in your living room and pull up the actual study or report and read it yourself, from soup to nuts. Your local newspaper might run a 600-word story about a speech some politician gave. The internet meant that you could watch the entire speech, unfiltered, and draw your own conclusions.

Instead of relying on a small number of information gatekeepers, you now had direct access to data. So you no longer had to rely on what the media told you about, say, crime. You could pull up the FBI crime stats and look at the numbers with your own eyes.

But it hasn’t worked out that way.

The internet has made all of that data readily available to people. And it turns out that often there is too much of it and it is too complicated for normal non-experts to understand. But the bigger problem has been the sheer volume of noise that the internet gave rise to. The noise overwhelmed the information, accelerating the decline in trust in institutions. The net effect was to make the populace as a whole less tethered to facts and data—and more animated by folk stories and something like an oral tradition.

We’re going to delve deep into all of this.

But first I want you to close your eyes and imagine being Mike Johnson.

You’re the speaker of the House of Representatives. One of the most powerful people in the world. Second in line to the presidency. And your job now requires you to spend hours on the phone with Vivek Ramaswamy at night, trying to explain politics to him and begging him not to shut down the federal government.

Yes, my friends, we are headed to the Bad Place. But there will be some entertaining diversions along the way.

1. Folklore

This Matt Pearce essay [https://mattdpearce.substack.com/p/jour ... urvival-in] brought me up short because it hits on a truth so profound that I can’t believe it never occurred to me before:

This. This is it, right there.The result of all of this [changing economics of media] is a growing consumer alienation from the actual sources of information, a return to a kind of folk-story society ripe for manipulation by demagogues who promise simplicity in an increasingly complex world.

We are now a folk-story society. The drones. The immigrants eating cats and dogs. The crime wave and “economic hardships” that haven’t been real since 2022.

It’s all folklore. Stories that a post-literate people pass on to one another in the oral tradition.

I cannot recommend Pearce’s essay enough. You should read it all. But I’ll give you a rough précis of his argument.

* In journalism, reporting has always been expensive to produce relative to opinion.

* The internet radically reduced the cost of producing opinion while only marginally reducing the cost of reporting—thus exaggerating this age-old imbalance.

* This economic reality increased the relative percentages of media outputs—thus greatly increasing the total percentage of the information pie that is made-up opinion.

* As the “opinion” percentage swelled and crowded out reporting, society normalized this phenomenon and re-anchored its expectations and tolerances.

* This re-anchoring leaves people expecting that opinion, rather than reporting, will be their primary source of information.

I’m saying “opinion” but Pearce just says “bullshit.” What we’re talking about is not just professional opinion writing, but published opinions by anyone in any format. This universe of content that runs from, say: this newsletter, to the New York Times editorial page, to National Review, to the Epoch Times, to Macedonian fake news orgs, to individual posters on Facebook, to Twitter bots.

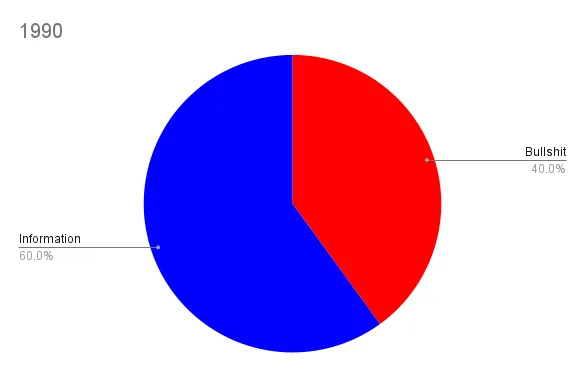

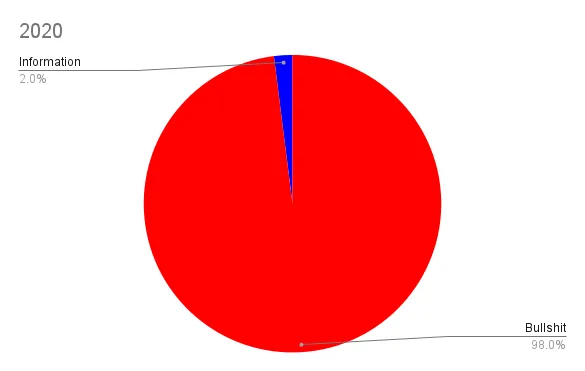

These charts are not to scale and I’m just making up numbers, but imagine the total output of “media” published in America in 1990 and 2020. It might look something like this:

In this sea of opinion/bullshit, people today are much less likely to hit upon genuine information than they were 30 years ago. This bedrock fact means that they’ve become acclimated to relying on opinion/bullshit.

And so instead of advancing society’s understanding of the world around us, the net effect of the internet has been to make us more primitive. More reliant on folklore, passed from person to person.

Ask yourself this: Could a story like immigrants eating dogs and cats have driven the 1992 election? Or even the 2000 election? I don’t think so.

This isn’t to romanticize the past. Demagoguery has always had a place in politics: the Red Scare, the Southern Strategy, Willie Horton.

But could a presidential candidate in the past have made up a totally fake story that contained not even a kernel of truth—and even admitted that it was fake, in real time—and had that story been so impactful?

Again: I don’t think so.

Pearce’s big insight is that this new world is ripe for demagogues because they thrive in societies that run on folk stories. The demagogue’s lies spread from person to person and even if the demagogue is conclusively exposed as a liar, no one believes the exposure.

2. Viral

If liberal society is an organism, a demagogue is a virus. The demagogue takes advantage of the freedoms afforded by liberalism to attack the host. Sometimes, if the demagogue is virulent enough, it can kill the society.

Over time, liberal societies build up antibodies to demagogues. The accumulation of such antibodies are one reason that the longer a liberal society endures, the more likely it is to survive challenges. Relatively new liberal societies are vulnerable because they have not had the time to build up antibodies. Old liberal societies are more robust.

These antibodies come in many forms: laws, traditions, institutions, civil society, an independent media.

We once hoped that the technological revolutions of the information age would become another antibody; another layer of protection. But it hasn’t worked out that way. Instead, it’s clear that the current state of technology has been like a radiation dose that kills off antibodies and compromises the organism’s immune system—in this case, leaving our society more vulnerable to demagogues than it has been in generations.

One last thing: There’s an even broader lesson here about progress and contingency.

Go back to 1996 and the infancy of the public internet and you’d be hard pressed to find anyone who thought that the information age could take us backward as a society, making us less sophisticated, more dependent on folk stories, and more susceptible to demagogues.

Which highlights a truth: We ought to be exceedingly humble when anticipating the long-term consequences of large-scale change. When the earth shifts, things can develop in unexpected ways.

Another truth: Life is contingent and very few things are inevitable. The effects we discussed today came about because of specific choices and decisions made in America by businesses, courts, individual people, and governments.

Had we made different choices, then we might have come to a different place. China’s encounter with the internet, for instance, has been quite different from ours. In China, the internet has served to reinforce existing institutions and strengthen authority.