But see, all the facebook uncles out there who post the "oh YeAh!??!?!" memes every time it snows in like April.

an even more frightening perspective

-

Deleted User 89

Re: an even more frightening perspective

the variable effects at different locations is something happening in the relatively short-term (relative in the geological sense, not human lifetime sense)

the next ice age will undoubtedly come, likely after humanity has worn out its welcome

the next ice age will undoubtedly come, likely after humanity has worn out its welcome

-

Deleted User 89

Re: an even more frightening perspective

With a reported temp of 119 degrees Fahrenheit, Sicily may have just experienced the hottest temps ever on the continent of Europe

Re: an even more frightening perspective

Is Sicily on the content of Europe? How's that work?

Defense. Rebounds.

-

Deleted User 89

Re: an even more frightening perspective

what other continent should it belong to?

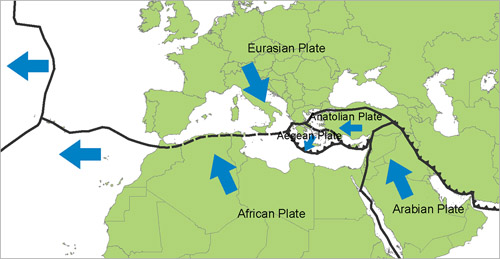

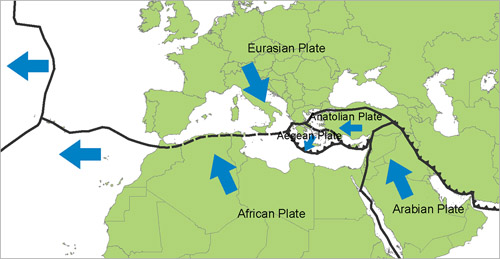

edit: i didn’t realize it was literally part of the European tectonic plate...figured it’d have been more like the Anatolian and Aegean plates

learn something new every day

edit: i didn’t realize it was literally part of the European tectonic plate...figured it’d have been more like the Anatolian and Aegean plates

learn something new every day

Last edited by Deleted User 89 on Thu Aug 12, 2021 2:01 pm, edited 1 time in total.

Re: an even more frightening perspective

maybe it shouldn’t be Europe, since Italy is literally trying to kick it off the continent

-

Deleted User 89

Re: an even more frightening perspective

from NatGeo:

A disaster can be long-expected and still come faster than expected.

People have been forecasting a long-term drying of the West for well over a decade. By this spring, as Alejandra Borunda wrote for us at the time, it was pretty clear that the water level in Lake Mead (pictured above), behind Hoover Dam, would drop below an elevation of 1,075 feet this summer, obliging the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to declare a water shortage on the Colorado River for the first time since the dam was built in the 1930s.

And yet when officials did just that yesterday, on a day when the news was consumed with the sudden collapse of Afghanistan, it still came as a bit of a shock.

Arizona farmers will suffer first, as the state loses nearly a fifth of the water it gets from the Colorado. But Nevada will take a hit too. And if the drought wears on, and Lake Mead continues to drop, cuts are coming to the water supply of other states, including California.

A long-feared reckoning is at hand. The “megadrought” is likely to wear on. "It’s really climate change that pushed this event to be one of the worst in 500 years,” Columbia University climate scientist Ben Cook told Borunda.

People have been forecasting a long-term increase in wildfires in the West for a long time too.

We’ve been watching it happen. Between 1983 and 2001, according to statistics from the National Interagency Fire Center, an average of 3.24 million acres a year burned in the U.S. Between 2002 and 2020, that figure more than doubled, to 7.21 million acres a year.

Drought promotes fire, climate change promotes both. This long hot summer has felt a bit like a doom cycle. Yet the path to limiting climate change is clear, and we’re starting to stumble down it. The path to healthier, less fire-prone forests is clear too: As scientists have been telling us for decades, we need to unlearn the lesson we absorbed from Smokey Bear, that all fire is bad, and allow controlled, prescribed burns back into the woods to clean out the excess fuel—like the Native Americans used to do.

At the same time, as Jennifer Oldham writes for Nat Geo this week, we need to pay more attention to Smokey Bear (pictured above at L.A.’s Griffith Park). The septuagenarian bear’s handlers are working hard to update his messaging for a younger and more diverse audience.

What?

Humans ignite more than 80 percent of all wildfires, Oldham explains, and 97 percent of all fires that threaten homes, in large part because of the American penchant for building homes in the woods. No spark, no wildfire—and with our burning of leaves on windy days, our undoused campfires, and our ill-placed fireworks, we provide most of the sparks.

Sometimes we need to find room in our mind for truths that may sound contradictory. Our problems feel overwhelming, of the kind that only concerted action by governments can solve—Western forests need cleaning, Western water use needs reforming, the whole global energy system needs changing—and yet our actions as individuals still matter.

Maybe, if we can manage not to lose heart, some good changes too will come faster than we expect.

A disaster can be long-expected and still come faster than expected.

People have been forecasting a long-term drying of the West for well over a decade. By this spring, as Alejandra Borunda wrote for us at the time, it was pretty clear that the water level in Lake Mead (pictured above), behind Hoover Dam, would drop below an elevation of 1,075 feet this summer, obliging the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to declare a water shortage on the Colorado River for the first time since the dam was built in the 1930s.

And yet when officials did just that yesterday, on a day when the news was consumed with the sudden collapse of Afghanistan, it still came as a bit of a shock.

Arizona farmers will suffer first, as the state loses nearly a fifth of the water it gets from the Colorado. But Nevada will take a hit too. And if the drought wears on, and Lake Mead continues to drop, cuts are coming to the water supply of other states, including California.

A long-feared reckoning is at hand. The “megadrought” is likely to wear on. "It’s really climate change that pushed this event to be one of the worst in 500 years,” Columbia University climate scientist Ben Cook told Borunda.

People have been forecasting a long-term increase in wildfires in the West for a long time too.

We’ve been watching it happen. Between 1983 and 2001, according to statistics from the National Interagency Fire Center, an average of 3.24 million acres a year burned in the U.S. Between 2002 and 2020, that figure more than doubled, to 7.21 million acres a year.

Drought promotes fire, climate change promotes both. This long hot summer has felt a bit like a doom cycle. Yet the path to limiting climate change is clear, and we’re starting to stumble down it. The path to healthier, less fire-prone forests is clear too: As scientists have been telling us for decades, we need to unlearn the lesson we absorbed from Smokey Bear, that all fire is bad, and allow controlled, prescribed burns back into the woods to clean out the excess fuel—like the Native Americans used to do.

At the same time, as Jennifer Oldham writes for Nat Geo this week, we need to pay more attention to Smokey Bear (pictured above at L.A.’s Griffith Park). The septuagenarian bear’s handlers are working hard to update his messaging for a younger and more diverse audience.

What?

Humans ignite more than 80 percent of all wildfires, Oldham explains, and 97 percent of all fires that threaten homes, in large part because of the American penchant for building homes in the woods. No spark, no wildfire—and with our burning of leaves on windy days, our undoused campfires, and our ill-placed fireworks, we provide most of the sparks.

Sometimes we need to find room in our mind for truths that may sound contradictory. Our problems feel overwhelming, of the kind that only concerted action by governments can solve—Western forests need cleaning, Western water use needs reforming, the whole global energy system needs changing—and yet our actions as individuals still matter.

Maybe, if we can manage not to lose heart, some good changes too will come faster than we expect.

Re: an even more frightening perspective

https://strangesounds.org/2021/08/high- ... lting.html

I have no idea what this source is or how reliable it is...but its kind of interesting.

I have no idea what this source is or how reliable it is...but its kind of interesting.

Just Ledoux it

-

Deleted User 89

Re: an even more frightening perspective

they cite a Nature article...so there’s that

will definitely have to check it out

will definitely have to check it out

-

Deleted User 89

Re: an even more frightening perspective

https://www.usnews.com/news/us/articles ... ional-park

A large swath of Denali National Park, one of Alaska's premier travel destinations, has closed for the summer tourist season weeks early after heightened landslide activity from excessive thawing of a mountain slope made the park's only access road unsafe...

A large swath of Denali National Park, one of Alaska's premier travel destinations, has closed for the summer tourist season weeks early after heightened landslide activity from excessive thawing of a mountain slope made the park's only access road unsafe...

-

Deleted User 89

Re: an even more frightening perspective

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-ne ... 180978519/

Europe’s Extreme Floods Are ‘Up to Nine Times More Likely’ Because of Climate Change

Europe’s Extreme Floods Are ‘Up to Nine Times More Likely’ Because of Climate Change

Re: an even more frightening perspective

Though apparently it might contained by the East troublesome burn scar, go figure

-

Deleted User 89

Re: an even more frightening perspective

all i know is that this air quality and smoke from the west has gotten old

if this is any sort of new normal, Utah won’t be for me for much longer...job be damned

what’s the point of living here if you can’t even enjoy the natural wonders?

if this is any sort of new normal, Utah won’t be for me for much longer...job be damned

what’s the point of living here if you can’t even enjoy the natural wonders?

-

Deleted User 89

Re: an even more frightening perspective

My wife took me fly fishing on our first date. I’d spent my adult life in the mountains, huffing up lupine trails and clambering over granite boulders, eager to gulp that high-country air. But I’d never tossed a drake or a tiny blue wing olive into a riffle on a bend in a mountain stream. This woman had, and it had transformed her.

As the icy Snake River pushed against my knees, and the hot southern Idaho sun baked my shoulders, fishing began to change me, too. My future partner showed me the little cases that caddisfly larvae build on stones. She taught me to spot barely perceptible shifts in current and to tell the difference between whitefish and cutthroat trout just by the way each tugged on my line. Over the next 20 years, we’d spend hundreds of hours on the water, in Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington. We fished across Canada and alongside bears in Alaska. I started seeing rivers and mountain ecosystems through new eyes. You could say I’d fallen in love twice.

So, I felt a sharp pang when writer Christopher Solomon detailed all the ways climate change may spell doom for many freshwater fish. As winters warm and snows come less often, rivers grow too thin and hot for species like trout and steelhead, which need rushing frigid currents. Some die outright, while others grow more susceptible to disease. The bugs they eat are disappearing, too, and native species are hybridizing with others. (Pictured above, fly-fishing guide Hilary Hutcheson with her family; below, a distinctive westslope cutthroat trout, Montana’s official state fish, which is threatened by hybridization.)

Freshwater fish went extinct twice as fast as other vertebrates in the 20th century. Forty percent of North American inland fish are still imperiled. Brook trout in Virginia are retreating higher into the Shenandoahs and may keep doing so until they’re gone. Brook trout in Wisconsin are expected to vanish from 70 percent of their waters before my teenage daughter is my age.

This type of loss is insignificant in the face of deadly wildfires, menacing heat waves, more powerful hurricanes and extended drought. A less diverse array of fish species will persist, and there are small signs of hope. Planting more trees could shade and cool water, for example. But, as Solomon writes, 700 million people around the world fish, and these shifts are a reminder that climate change is remaking the world in subtler ways, too, altering how “we move through our daily lives.”

As the icy Snake River pushed against my knees, and the hot southern Idaho sun baked my shoulders, fishing began to change me, too. My future partner showed me the little cases that caddisfly larvae build on stones. She taught me to spot barely perceptible shifts in current and to tell the difference between whitefish and cutthroat trout just by the way each tugged on my line. Over the next 20 years, we’d spend hundreds of hours on the water, in Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington. We fished across Canada and alongside bears in Alaska. I started seeing rivers and mountain ecosystems through new eyes. You could say I’d fallen in love twice.

So, I felt a sharp pang when writer Christopher Solomon detailed all the ways climate change may spell doom for many freshwater fish. As winters warm and snows come less often, rivers grow too thin and hot for species like trout and steelhead, which need rushing frigid currents. Some die outright, while others grow more susceptible to disease. The bugs they eat are disappearing, too, and native species are hybridizing with others. (Pictured above, fly-fishing guide Hilary Hutcheson with her family; below, a distinctive westslope cutthroat trout, Montana’s official state fish, which is threatened by hybridization.)

Freshwater fish went extinct twice as fast as other vertebrates in the 20th century. Forty percent of North American inland fish are still imperiled. Brook trout in Virginia are retreating higher into the Shenandoahs and may keep doing so until they’re gone. Brook trout in Wisconsin are expected to vanish from 70 percent of their waters before my teenage daughter is my age.

This type of loss is insignificant in the face of deadly wildfires, menacing heat waves, more powerful hurricanes and extended drought. A less diverse array of fish species will persist, and there are small signs of hope. Planting more trees could shade and cool water, for example. But, as Solomon writes, 700 million people around the world fish, and these shifts are a reminder that climate change is remaking the world in subtler ways, too, altering how “we move through our daily lives.”

Re: an even more frightening perspective

ill tell you whats not dying. flies. I have never in my life had a summer with so many flies around. its insane. ive filled up over a dozen or more fly bags to the brim. they are everywhere. never have i seen this amount of these things

Just Ledoux it

-

Deleted User 89

Re: an even more frightening perspective

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/07/us/g ... ality.html

Booming Utah’s Weak Link: Surging Air Pollution

A red-hot economy, wildfire smoke from California and the shriveling of the Great Salt Lake are making Utah’s alarming pollution even worse...

Booming Utah’s Weak Link: Surging Air Pollution

A red-hot economy, wildfire smoke from California and the shriveling of the Great Salt Lake are making Utah’s alarming pollution even worse...